“My job is questioning photography”, laughs Thomas Ruff, a star artist whose prints are sold at extremely high prices at auctions such as Christie's. He visited Japan for his solo exhibition “Two of Each” at Gallery Koyanagi in Ginza, held from October 18 to December 13.

Ruff’s relationship with Gallery Koyanagi dates back to his solo exhibition there in 1998, and this marks his first solo show at the gallery in 11 years. The exhibition features his past iconic works alongside the Japan debut of “flower.s” and “untitled#”, making it resemble something of a mini-retrospective.

Many may have seen Ruff’s work at the large-scale retrospectives held in 2016 at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, but it is extremely difficult to describe his style in a single word.

In his early iconic “Portraits” series, photographs of people resembling ID photos were enlarged to a massive 210×165 cm, offering viewers an experience that elevates portrait photography to a different stage. In his “nudes” series, he sourced images from online pornographic sites, heavily blurred them, and then printed them on a similarly gigantic scale, challenging notions of originality, sexual expression, and even the very resolution of photography itself.

In his “Cassini” series, he also used images of Saturn and its moons captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, manipulating the photos provided by NASA to create images that appear almost like computer-generated graphics.

In a way, his work has been a continual inquiry into questions such as “What is photography?” and “What defines a photographer’s originality?”.

It is widely known that he has studied photography from the great masters of modern photography, Bernd and Hilla Becher. This couple taught photography at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany, and mentored students who would go on to form a major movement in art photography from the 1980s onward, known as the Becher School.

Among those students are Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, and, of course, Thomas Ruff himself. All of them stars of the industry. However, Ruff remembers how much he suffered under Becher’s guidance in the beginning.

“I grew up in the countryside in a small town. My favorite thing was taking photographs with my Nikon camera. I just had access to photo magazines, and that was my world of pictures. I took photographs during holidays in Greece and Italy, and I was pretty happy with them (laughs).

Until I then applied to the Art Academy. Becher’s world was the opposite world of photography than mine. Mine was colorful, pretty kitsch, a lot of sunsets and things like that, and the Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher’s world was black and white, very straightforward, very simple, kind of industrial. I was shocked, I didn’t know what to do”.

Bernd told me that my photographs were not my own photographs but imitations of photographs that I saw in the magazines. At a certain point I realized, “Ok, yeah, they’re right, I’m wrong”. Becher told me: “Ok, you should look at the books of Walker Evans, so on and so on”. I then started looking at the history of photography.

I was in two classes: all the different medias were together, so there were painters, sculptors. I was in a kind of shock, so, I just watched my friends working. Very slowly I started using the camera again. Of course, in the Bernd Becher style. I think the first thing I chose was a chair, pretty boring. Black and white, of course!”.

Ruff managed to escape from the Becher’s black and white industrial dogma when he started photographing the work of his classmates in colour.

“Some friends of mine, sculptors and painters, they were the first ones to invite me to group exhibitions and they needed photographs of the works for the catalogue, and they needed color photographs. I already had a 4×5-inch camera. But then they had already showed me the books of new, American colour photographs, the new colour photography. That was really “wow”, I continued shooting in colour.

Then I learned how to take beautiful 4 by 5 inch ektachrome film, then I photographed one of my interiors in colour and liked it much better than the black and white one. I showed my first photographs in ektachrome to Bernd Becher, and he said: “Oh, Thomas, you’re right. It looks so much better in colour, just skip black and white and continue in colour”. Since then, I continued shooting in colour”.

Ruff’s subsequent rapid rise is well known. Photographers of the Becher School, including him, are often described as creating “photography that asks viewers to look at the photograph itself, rather than its subject matter”. But what does Ruff think of such assessment?

“That’s just the vanity of all photographers. They don’t want people looking through their photographs into reality. Say, there is a seascape. But the artist wants to hear: “Oh, this is a seascape by Hiroshi Sugimoto”.

But of course, reality is a big part in this genre of photography. That probably has something to do with the perception of the state of photography used to be in, because everybody thought, “Ok, maybe only as a documentary, photography should probably be accepted as art first degree, not as art second degree”. We all tried to switch that thing. There were collectors that did not look at photographs, they only collected paintings and sculptures or drawings, they thought photography is so not worth looking at.

But with the first portraits I took, when they were on display at a gallery or at the art fair, even those collectors, they were shocked, they could not pass. It was so different to painting, it had a different kind of precision, that they could not ignore it anymore. I think that was the turning point. Then my colleagues followed with the large-scale images”.

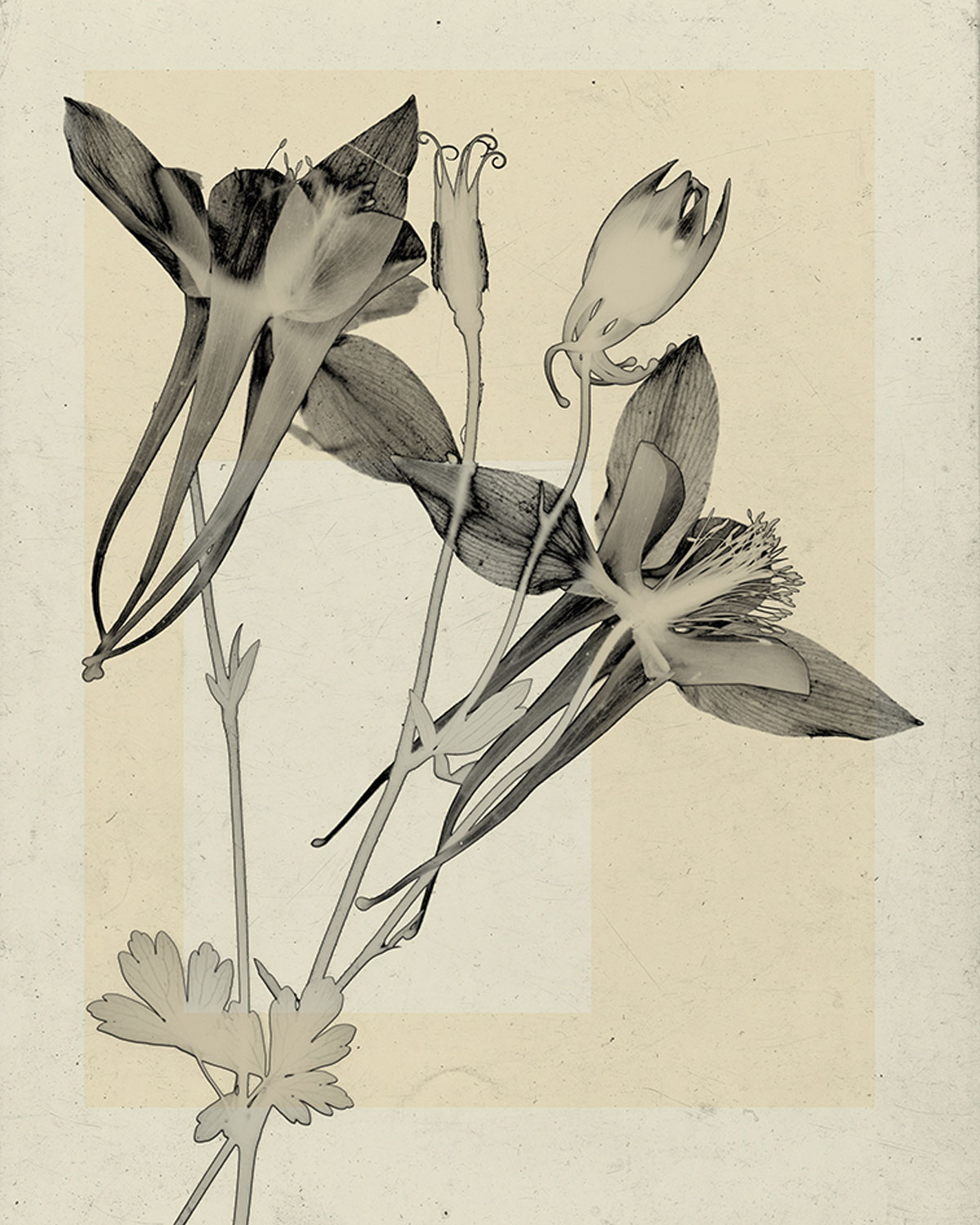

The exhibition at Gallery Koyanagi features two of Ruff's most representative series from the past, as well as two works from each of two series that are being shown in Japan for the first time. First, "flower.s" is a work in which flowers and plants were arranged on a light table and photographed with a digital camera, then a solarization effect was applied to the image on a computer, reversing the light and dark areas.

And in his recent series, "untitled#," Ruff picked up his camera for the first time in a long time, rotating and vibrating wire structures and photographing them with long exposures. This brings the experimental photography of the 1950s and 1960s into the present day, showcasing the linear play of light and shadow. As a unique photographer who sometimes uses a camera and sometimes doesn't, what possibilities does Ruff still see in "classical photography"? Or does he see it as being on the verge of extinction?

“No, I think there is still enough space for it. A lot of great photographers are still using the medium in a really good and proper way, like Edward Burtynsky. I cannot name all of them, but they do fantastic work, and I would say I am the exception. I don’t believe in photography (laughs). Of course, I love photography. But I have some questions concerning photography so I am a bit out. But there are still enough photographers. It will not die”.

Rei Masuda, the chief curator of Ruff’s exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, describes Ruff's "expansion of photography" as follows:

“In Ruff's earliest work, the Portrait series, he photographed people's faces neutrally from the front, like passport photographs, and turned them into gigantic prints measuring nearly two meters in height. He focused not at classical issues such as what (who) is depicted, how the photograph was taken, and what intention was behind it, he foregrounded the existence of the medium of photography itself (although this was a kind of a forceful technique, in that the photographs were physically enlarged to give them a greater presence), and attempted to get viewers to think about photography itself. In this way, Ruff's expansion of photographic expression was a continuous process of re-examining the medium of photography itself from various angles.

Each of his series, for example, the jpeg series, addressed issues of image resolution, perception, and recognition, while the “nudes” and “Substrate” series question the very nature of representation as an object of desire. One might say that Ruff's work is a gradual redrawing of the contours of the photographic medium”.

Although Ruff started out with large-scale portraits, he is moving away from both straightforward photography and the classic image of a photographer.

“In terms of my intent in photography, I don't shoot straight. If I shoot straight, I add some questions to the image. Because the last twenty years I did not shoot at all straight, but used found images I processed, images in which I worked with virtual reality. That’s why I say I’m not a classical photographer. But there is definitely still space for classical photography”.

Rei Masuda of the National Museum of Modern Art, describes the current exhibition at Gallery Koyanagi as a "pleasant betrayal".

“This time, Ruff is presenting two new works ("flower.s" and "untitled#") that include the process of taking photographs himself using a camera for the first time in a long time. While this in some ways betrays expectations, it is consistent in that Ruff continued to reexamine the photographic medium itself from various angles, thereby continuing to expand our concepts of photography and of being a photographer.

It reminded me that the joy of viewing Ruff's work lies in the experience of casually presenting questions from a different angle, stimulating and activating something within us as viewers, and slightly updating our approach to the medium of photography, or our way of looking at things and the world”.

Ruff has continued working with found images for nearly twenty years, but why is he so attracted to images taken by others?

“There are different reasons for using found images. The first time I used found images was when I wanted to photograph the stars. At that time, I had realized that even though I am professionally educated, I cannot shoot the stars because I had only this one telescope. So, I asked the observatory to give me a negative. It’s a question about the quality of the image. Sometimes I just need help. If I find help in somebody else, I accept it”.

Ruff, who is constantly renewing his photographic expression, says, "everybody should have their own vision".

“If you look at the world of photography, you'll see that each photographer has their own specialty. For example, Sebastião Salgado's role could be said to be to raise awareness of global environmental issues through photography. The next one is working on technology, so everybody has his job. My job is questioning photography. Nobody can do all of it, and it doesn’t make sense, it would not make sense to”.

Ruff describes himself as a photographer who exists "outside of photography". But what is his definition of photography?

“There are several keys to this. Even though you could say, a 100 years ago there was one way and one belief on what photography should or could do. Photography was invented and immediately was used or misused for all different kinds of interests. I would say there is no proper one way to use photography, I would say there are many correct uses as there are photographers. So, everybody should have their own vision and you should not say: “Oh, this is not correct photography. This is correct photography”. It doesn't make sense to dictate the final definition of photography. That’s just bullshit”.

After finishing the interview, we began chatting and talked about his extended stay in Japan. He cheerfully recounted relaxing in the hot springs at the foot of Mount Fuji, as well as a trip to Osaka. I asked him if he ever takes photographs at such times. “Well, actually...”, he replied and pulled out his smartphone, starting to show me his photo gallery.

There were photographs of Japanese landscapes, architecture, and shinkansen trains. The monochrome processed photographs had a calculated composition that made them look so industrial and Becher-esque that it was almost funny. Seeing Ruff show these with such joy, I realized that he truly loves photography and is constantly moving between the inside and outside of photography.