“The visitors of the exhibition filled three guest notebooks with comments. The depth and passion of those comments surprised even the gallery owner, who said, “We never had a photo exhibition like this before”.

So says photographer Yoshinori Onda. His photo exhibition “Forever!! Olive Girl” (May 20 - June 7) at Gallery EM in Nishi-Azabu showcased the fashion photography he created for the magazine “Olive”. Despite very little advance publicity, the show attracted a large crowd. When I visited the venue a few days before the final day, I found myself having long conversations about the photographs with complete strangers — the place felt like a unique community, quite unlike your typical photo exhibition.

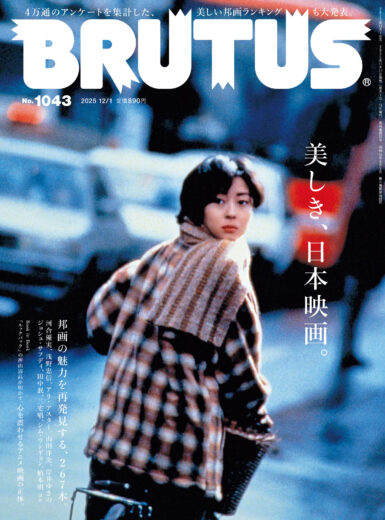

Some readers may need an explanation of what “Olive” is. It was a women’s fashion magazine published from 1982 to 2003 by Magazine House, the same publisher as BRUTUS.JP, which hosts this column. “Olive” initially debuted as a special edition of “Popeye” in 1981, before launching as an independent magazine in 1982.

With the tagline “Magazine for Romantic Girls”, “Olive” positioned itself not as a magazine for adult women, but as a fashion magazine for the fashionable city girls. The magazine’s unique, fantastical worldview influenced many people, inspiring dedicated fans of both genders. I count myself among them — not an “Olive girl”, but rather an “Olive old man”.

But why did Onda, an iconic photographer of “Olive” (which ceased publication 22 years ago), decide to hold an “Olive” photo exhibition now?

“Yamato Shiine contacted me and told me: “You should do an “Olive” photo exhibition”. If he hadn’t said that, this exhibition might never have happened”.

Yamato Shiine was the editor-in-chief of “Olive’s” first issue. He is now an author, known for numerous works mainly based on his experiences during his time at Magazine House, such as “Yukio Mishima on Heibon Punch” and “Popeye Story 1976–1981”. Shiine wrote the text, or, rather, a manifesto, that was displayed at the photo exhibition venue, titled “The Birth of the Olive Girl! Where Does the Gaze of Yoshinori Onda Come From?”. In it, he writes:“In Onda’s fashion photographs, girls on the verge of adulthood are enjoying a world of ‘involuntary memory’. There’s none of that clumsy ‘deliberate memory’ like cramming for exams”.

However, although Onda has been widely acclaimed, he himself has never held a large photography exhibition before. “I have never really thought about things, sich as having a particular style as a photographer, or about what turns a photographer into an author. This concept doesn’t exist for me. Both my professional work and my private photographs – I am proud to see both as them as me”.

Onda’s background is one that has run through the golden age of Japanese magazine culture, particularly magazines centred on photography. Born in 1948 in Kichijoji, Tokyo, Onda’s family home was a photography studio. However, he had no intention of becoming a photographer; he entered the Faculty of Business at Aoyama Gakuin University. At the time of his enrolment, the campus was in the midst of student unrest, and most classes were cancelled. It was through a friend’s invitation that he joined the university's photography club, and this became the focus of his university life.

Since those days, Onda was absorbed in photography. He sent his work to Shoji Yamagishi, the renowned editor-in-chief of the most influential photography magazine at the time, “Camera Mainichi”. Soon, his work was published. Onda began to take on commercial assignments. Starting with “So-en” (published by Bunka Publishing Bureau), he moved on to the then brand-new magazine “An An” and contributed to the very first issue of “Popeye”, pushing his way down the mainstream of Japanese fashion and culture magazines. He went on numerous overseas shoots for “Popeye”, and what he learned from those was that “the most important thing in magazine photography is flexibility”.

His encounter with “Olive” began with an invitation from Shiine.

“Shiine, who had been working on “Popeye”, mentioned he was going to launch “Olive”, so I joined from the first issue. However, the truth is that, at first, what the two of us wanted to do didn't really match, and I left after just a few issues”.

After Miyoko Yodogawa became the third editor-in-chief of “Olive”, she invented the idea of a “Romantic Girl”. This also meant a fresh interpretation of ‘kawaii’ concept. Onda sympathised with this direction and re-joined “Olive”.

“In one of the first meetings Yodogawa said: “When I was walking in Daikanyama, I saw three or four junior high school girls holding hands and looking like they were having so much fun. It was really cute”. And I thought, yes, it really is. That made me feel that, for “Olive”, it wouldn’t do to simply take photos of models standing around in cute clothes. I also wanted to shoot something new and different from what I had done before, so I decided I’d try to bring out the individuality of each model. I tried not to impose anything, nor to dictate their poses or locations; instead, I left it to the models to do whatever they wanted to do”.

Thus began the honeymoon of Onda and “Olive”. With “Olive” published twice a month, he continued to shoot an average of around 20 pages per issue from 1986 to 1989. Moreover, in those days, two out of every three covers were also by Onda.

“Olive” was a kingdom of dreams, wasn’t it? The staff, myself included, were young and capable, and we gave it our all. We discovered many new talents, like Cecilia Dean, who later made it big. But after about five years working on “Olive”, I felt I had nothing more to give”.

Mariko Chikada, a stylist who worked with Onda on many photo shoots, describes his photography in this way:

“What stands out in both his photography and his character is his outstanding openness. And perhaps understanding of the atmosphere, too. Rather than insisting on “I want to take this kind of photo” or “It must be like this”, he had a broadness of spirit to accept whatever came — the light and wind of the day, the feelings and expressions of the models, spontaneous happenings or accidents, and then jam with them like in a musical session. In Onda’s photographs for “Olive”, running and jumping do stand-out, but it’s not just that the movement looks cute; it actually conveys something intangible, something in the air, and I think there are many people whose hearts were moved by that. When you can sense that air that can’t be seen but is there, perhaps that is when a special feeling or way of thinking comes into play”.

Afterwards, Onda started working more for “An An”, following Yodogawa's move to become its editor-in-chief, and also became involved in the launches of “EDGE”, “Tokyo Calendar”, and “LEON”.

“I am not actually that interested in work outside the editorial field. Being involved with a debut issue, shooting the cover for a debut issue, has always had great significance for me, and with every new magazine I’ve made sure to try something new — to deliberately change what I was doing, magazine by magazine. I always want to express something different from the day before, and even now I try to keep up with that approach. That’s why, having given my all to “Olive”, I felt ready to move to the next stage. But now, having actually held this exhibition, I realise once again that “Olive” really is the root and the origin of my photography”.

Mariko Chikada also feels there is something special that lives inside “Olive”.

“If one of the features of timelessness is that “something dwells within it”, then that is surely the case with “Olive”. Pre-calculating, being satisfied with little, taking shortcuts — none of this had place at all in “Olive”. It was always a magazine that tried to feel what cannot be seen amid all the different perspectives and layers, and I think that’s why it became more than just a magazine to look at or read — it became a magazine that connected with the senses, even the sixth sense”.

Now spoken of with such passion, “Olive” has become an extremely popular magazine at second-hand bookshops. Magnif, a used bookshop in Jimbocho that specialises in fashion magazines and bustles with overseas customers, is known for its well-stocked back issues of “Olive”. Yasunori Nakatake, the owner, says:

“Roughly speaking, the main criteria for the magazines we handle is how much influence they have had on fashion culture. In that sense, “Olive” is absolutely indispensable. I think it is a rare magazine that, with its unwavering cultural density, led the era for many years. As for the photography in “Olive”, especially during the “Lycéenne era” of the 1980s, it had a romantic charm, as though viewed through a fantastical filter – it really felt like peeking into another world, almost like being inside a story”.

After leaving his work with “Olive”, Onda tried working in New York.

“When I was about fifty, I thought I might try to work in New York and took my portfolio over there. At the time, I was also doing work for Armani, so I included that in my book and showed it to an agent.The work that got the best response was the work I did for “Olive”. They told me: “There is nothing like this in “Vogue”. “Vogue” pivots around concepts like maturity and sexiness, but “Olive’s” values were different. These days I think Tim Walker comes the closest to “Olive’s” way of seeing things. The New York agents responded well to my portfolio, but they said I’d have to live in the States, and that just wasn’t possible for me”.

The culture of Japanese fashion magazines, which originally took European and American magazines like “Vogue” as their model, has since the 1970s developed unique styles of its own. One symbol of this is “Olive’s” concept of ‘kawaii’, a value system distinct from the maturity and sexiness promoted by Western magazines – something realised in Onda’s imagery.

Nakatake of Magnif adds: “When I see overseas visitors who cannot read Japanese still being thrilled to pick up a copy of “Olive”, I am sure it has a visual appeal that transcends time period and nationality.In the same way, many of Onda’s other titles, such as “Popeye”, are eagerly purchased by overseas customers. Just as Japanese city pop music is currently being rediscovered worldwide, perhaps Japan’s once-rich magazine culture itself is now sought after as a valuable heritage”.

The manifesto displayed at the photo exhibition also declared proudly: “The sense and sensibility of cuteness created by Yodogawa, Onda, and Mariko now forms the underlying tone of subcultures all around the world”.