“If we have to divide people into artists and photographers, I would choose to call myself a photographer”, Keizo Kitajima says on the café terrace of the Nagano Prefectural Art Museum.

Currently holding a large-scale retrospective exhibition titled “Keizo Kitajima: Borrowed Place, Borrowed Time”, which opened on 29 November at the Nagano Prefectural Art Museum (running until 18 January 2026), recently Kitajima has not only presented this exhibition but in November also republished a newly reworked documentary series he shot in 1991 during the collapse of the former Soviet Union, which caused a stir at the time. Recently, he has also been actively involved in international projects, including shooting a campaign featuring Rihanna for Louis Vuitton and releasing a photobook through the American publisher Little Big Man.

I asked him about his path, which displays an unprecedented cross-disciplinary range for a Japanese photographer, spanning art, documentary, and fashion.

Keizo Kitajima is widely known for having begun his career at the legendary “Workshop Photography School”. Founded in 1974 with an extraordinary lineup of instructors including Shomei Tomatsu, Nobuyoshi Araki, Masahisa Fukase, Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama, and Norimitsu Yokosuka, the school closed after only three years, yet left a profound mark on the history of Japanese photography.

“Even after entering university, I had no vision for the future at all. I didn’t know what kind of job I wanted. I only had this vague image that if I just went from high school to university in an automatic way, I’d end up getting a reasonably decent job along with everyone else.

When you’re young, you have all these boiling, murky feelings inside you, things you can’t get rid of, such as anger or pride. I felt that a way of life that suppresses those things would be boring. That’s when I decided to quit university and start photography. At that time, I saw an advertisement for “Workshop Photography School” in “Asahi Camera” magazine, and that pushed me to make the decision all at once”.

Kitajima looks back on the state of Japanese photography in the 1970s:“At that time, photography magazines were the main platform for photographers to present their work. There were many photography magazines, and even ordinary office workers would read “Asahi Camera”. Designers and photographers were glamorous professions. Myself, too, from junior high through high school, I was reading those magazines as well.

I saw Araki’s “Satchin” win the Taiyo Award (1964) and Daido Moriyama’s “Accident” series in “Asahi Camera”(1969) around the same time when I was in high school. When I thought I had no future prospects, I started to think, ‘”Maybe I’ll try photography”. But if I was going to quit university to do it, there was no other option but to commit fully. And that’s how I ended up entering Workshop Photography School”.

“Moriyama, Araki, Tomatsu, and Hosoe all had their own classes, but me choosing Daido Moriyama was actually a coincidence. What mattered, though, was that I had this completely groundless determination to become a photographer”.

At Workshop Photography School, Kitajima enrolled in Daido Moriyama’s class, drawn to the image of the photographer that Moriyama embodied.

“I thought a photographer was someone who wandered the streets aimlessly with a handheld camera and photographed whatever they liked. Like Takuma Nakahira or Moriyama. They weren’t photographers defined by their subjects, like those who photograph food, or cars, or sports, and so on... They were people who took photographs that awakened something unfamiliar, something unseen. Daido Moriyama was the prime example of that. If Daido Moriyama hadn’t existed, I might never have thought of becoming a photographer. It was the time of the emergence of photographers defined not by what they photographed, but by how they photographed”.

From the late 1960s through the 1970s, movements in photography centred on “how to photograph” emerged around the world.

In Japan, the rough, aggressive approach known as “Are, Bure, Boke” emerged, popularised by the photography magazine Provoke (founded in 1969) by photographers Takuma Nakahira, Yutaka Takanashi, and Daido Moriyama; in the United States, the “New Color” movement of the 1970s led by figures such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore; and in Germany, Bernd and Hilla Becher, who began teaching at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1976, were instructing students in a photographic methodology known as “typology”.

In other words, a period began in which global photography prioritised “How?” over “What?”. It was amid this context that Kitajima, together with Moriyama and others, established the independently run gallery Image Shop CAMP.

“I had thought that if I entered Workshop Photography School, a path to becoming a photographer would open up, but the school ended after three years, so suddenly I was back at zero. I had no idea how to become a photographer or what I should do. At that time, Moriyama approached me and said that if I had a space, a base where I could exhibit my work and sell what I photographed, I could remain a photographer. It was a real eye-opener for me (laughs). That’s how we ended up running Image Shop CAMP together.

Fundamentally, that way of thinking hasn’t changed at all even now. I basically believe that you have to do things by yourself. But at some points I did become anxious and asked Moriyama, “How do you make a living?”. He replied, “I don’t”. And I said, “But you live somehow”. He did. I thought, if I could be like him, that’d be fine (laughs).

Kitajima’s early works are also included in the current exhibition. Among them are rough photographs characteristic of the “Are, Bure, Boke” style.

“I entered Workshop Photography School in 1975, but by then Provoke had already ceased publication. Moriyama had already published “Shashin-yo Sayounara (Farewell Photography)”. Nakahira had already published “Kitarubeki Kotobanotameni (For a Language to Come)”. Both of them were at a stage where they were completely rejecting anything “Provoke-like”.

“What had originally been a form of resistance, a form of struggle, i.e. “Are, Bure, Boke”, had turned into an extremely fashionable trend. The blur and grain were no longer the result of events or accidents as subjects, but something handmade. People deliberately damaged film or manipulated prints in the darkroom. It became a purely visual matter. But once there’s a handmade element, the author’s intention inevitably enters the work”.

To reject darkroom work, Nakahira deliberately began shooting with colour slide film and sending it directly to the lab for development and presentation. If you press the shutter and send the film straight to the lab, your own hand doesn’t intervene. That’s how he photographed a deep blue sky and presented it simply as a blue sky.

Moriyama found Weegee in New York interesting, and in Japan, Katsumi Watanabe. They used strobe light, which eliminated the human author’s intention and the photographer’s emotions. In other words, it was the idea that an autonomous expression created solely by machines was possible. Essentially, a form of machinism.

At the moment ideas were emerging that would blow away handmade expressions like blur and grain, such as the total rejection of darkroom processes through colour slide film, or the elimination of authorial intent through equalising artificial light of strobes. That’s exactly when I entered Workshop Photography School. So, I already had no intention of doing blur-and-grain photography”.

During the 1970s, Kitajima frequently visited Okinawa and presented the photographs he took there.

“However, the problem of binary opposition inevitably arises: mainland Japan versus Okinawa, the photographer versus the photographed. But this issue of the one who photographs and the one who is photographed occurs no matter where you shoot. At that point, I began to think that perhaps New York might be different.

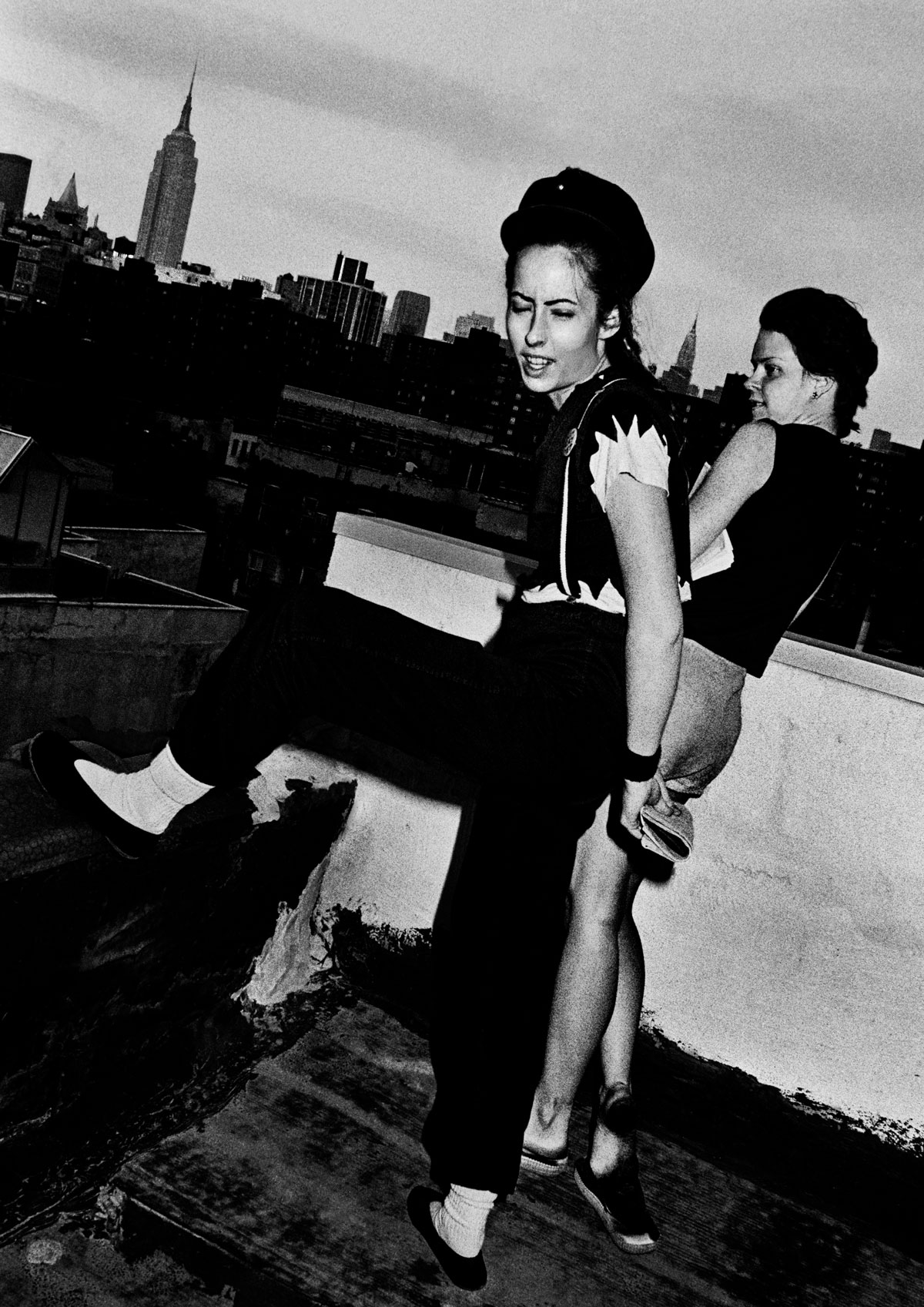

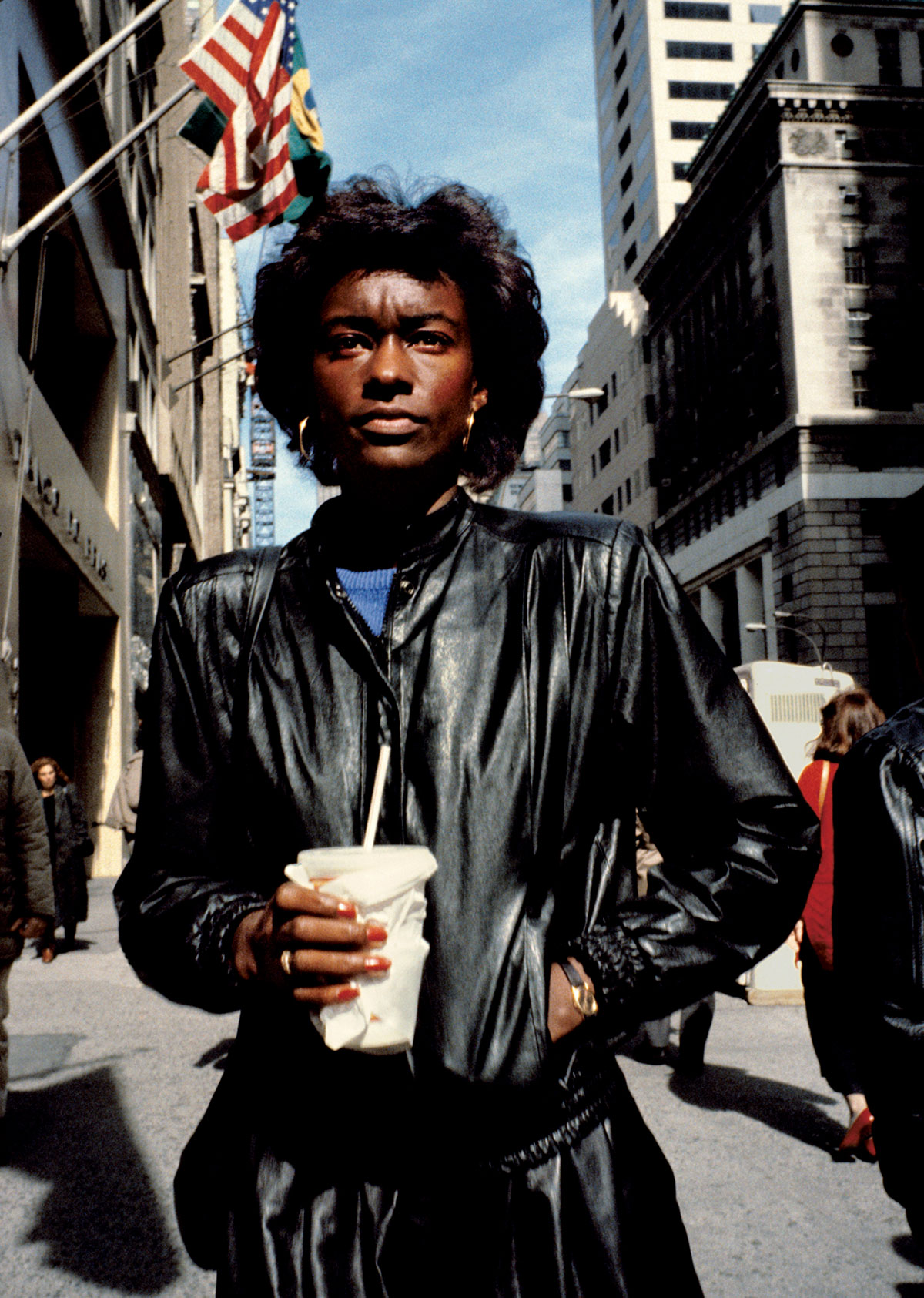

New York came to me through images and cinema as a city in ruins, almost the end state of an urban civilisation: above, the buildings as centres of economic and cultural power; below, something like the Third World. It was 1981, a time of severe economic downturn. I felt that this city might have the power to shift entirely this binary way of thinking between photographer and photographed.

When I actually moved to New York, there were all kinds of people there, and I felt like they weren’t all that different from me (laughs). I was a poor photographer, there were plenty of poor people in the streets, people collapsed on the pavement. It wasn’t a constant “Who are you? Who am I?” situation. I felt that they might be walking through the city with the same feelings as me”.

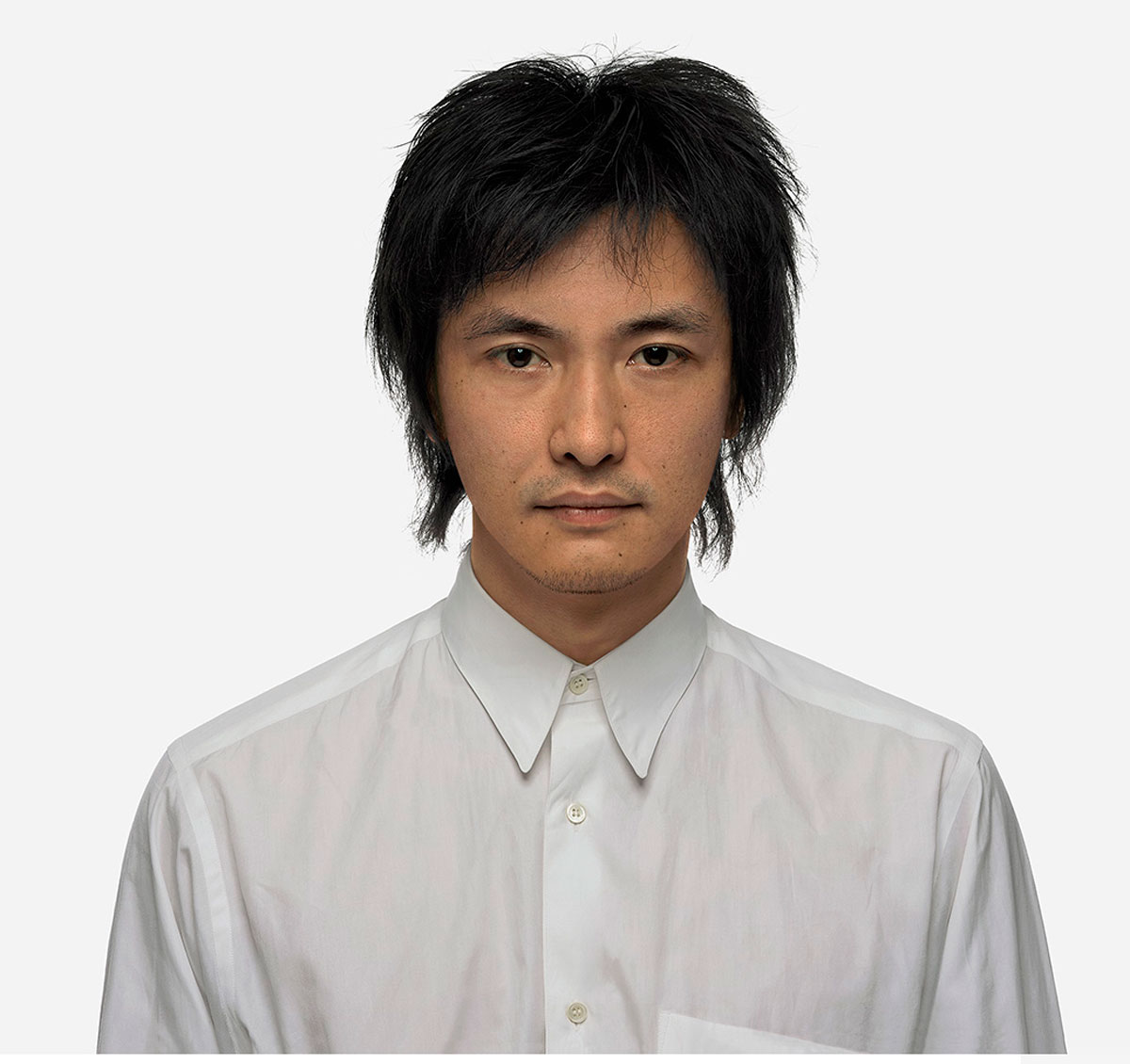

With the striking snapshot photobook “New York” (Byakuya Shobo), capturing the people of that city, Kitajima won the Kimura Ihei Photography Award. However, he began to think about elevating the act of photographing faces to the next level. After a long period of trial and error, the portrait series of ordinary people against a white background wearing white shirts was presented in 1996. The methodology of photographing the same subjects under identical conditions at one-year intervals attracted attention.

“After “New York”, I photographed in Eastern Europe, and also took close-ups of people’s faces on major streets in Seoul, but I started to feel a certain limitation in the act of photographing cities and people through street snapshots. I began to think that maybe it just wasn’t very interesting anymore.

I had been photographing people’s faces within the city, but I decided to separate the human face from the landscape and photograph them independently. That’s how I began the portrait series. So rather than my style changing drastically, it feels more like it was branching.

If we’re talking about portrait photography, when I really think about it, portraits were actually the medium I disliked the most (laughs). Portrait photography represents a person through a single idealised, symbolic image. But people exist in many states, from newborns to the elderly, and a single portrait functions as a device that reinforces identity. That runs completely counter to what I had been doing with snapshots. It’s like the system where, at a funeral, you display the most dignified photograph possible.

I felt that the very system inherent in portrait photography was a terrifying enemy. So, I decided to destroy the principle of homogeneity in portraiture by taking many photographs in the same format, making every single image equivalent. Portrait photography inevitably produces symbolism when there is only one image. But if the photographs differ only slightly, it becomes problematic: when you’re told “this is you”, both images are you — and yet neither of them is you. That is photography.

The portrait series was shot using an 8×10 camera with reversal film. I established a number of rules: first, the image would be horizontal, because vertical compositions increase symbolic power. White background, white shirt, photographing the same person every year. As the years progress, it becomes impossible to say, “The second year is bad, but the first year is good”. I deliberately eliminated all room for taste-based or value-based judgement”.

I regard Kitajima’s portrait series as a body of work that transformed the very concept of portraiture to a degree comparable with Thomas Ruff’s portrait series. It is less an experience of looking at faces than of encountering the photograph itself with overwhelming intensity. Kitajima once said in an interview, regarding the specimen-like finish of this portrait series, that he felt “interesting things became boring”, and now I asked him about the meaning behind that remark.

“For example, when you photograph people who appear strange to ordinary people in back alleys late at night in Shinjuku, some ordinary viewers may find them unusual, but I started to feel that this was not interesting at all. I think photography originally developed in that way: photographing rare things or distant things and showing them. That may be a healthy power of photography, but for me, that kind of interest eventually becomes tiresome.

For example, people wearing the latest, most extravagant fashion and freely expressing themselves may appear crazy, and plain-looking people in Eastern Europe may appear unusual, but how people appear is always relative. It is not something inherent to their appearance. I think photographs that say: “The way gay people dress late at night in Shinjuku is interesting” are boring.

In my landscape photographs, meaningless places are important, things like inexplicably white walls. It’s important that elements are included that cause meaning to collapse (laughs), or rather, that make meaning stumble”.

I asked Masashi Matsui, curator at the Nagano Prefectural Art Museum who planned Kitajima’s exhibition, how he intended to present Kitajima, whose subjects and shooting styles have changed so dramatically over time.

“In this exhibition, while we attempt an overview of Mr. Kitajima’s achievements over fifty years, we were determined not to create an exhibition that would relativise the photographer in a ‘specimen-like’ manner.

In particular, when exhibiting Kitajima’s work which repeatedly rereads past and present photographs as equivalent and continually requestions the meanings contained within them, uncritically applying the conventional retrospective format of arranging works chronologically risked obscuring its essential nature. For this reason, we slightly shifted the chronology and created a recursive exhibition space, allowing the exhibition itself to be ‘re-read’. In doing so, we believe viewers may stand on the same level as Mr. Kitajima and encounter the photographs with the same sense of discovery”.

In November, Kitajima exhibited his photographs of the former Soviet Union taken in 1991 at the new Tokyo photography gallery KOSHA KOSHA AKIHABARA, and released them as a photobook titled “USSR 1991” (new edition).

“I want to present the Soviet Union of 1991 in the present tense, and it isn’t my “past work”. Past photographs can always be edited in the present tense. Photography is that kind of medium. With portrait photographs, a picture taken ten years ago isn’t old and one taken this year isn’t new, is it? What I learned from that is that there are no old photographs in photography.

There was a time when photographers were absorbed into art history and began producing tableau-like photographs, but I find that boring. Photography has no past, present, or future, such divisions are inappropriate for photography. Photo history has become a history of artists, but there are countless things in photography that do not become part of artist history, and those are far more important”.

Masashi Matsui of the Nagano Prefectural Art Museum interprets Kitajima’s position in this way:

“In the Japanese photography world, from a certain point onward, photographic expression that entrusted itself to the personal narrative of the individual photographer seems to have formed a major current (of course, this is not to deny such photography, nor to claim that Mr. Kitajima’s photographs contain no such narratives at all).

But within this context, Mr. Kitajima has confronted head-on the issue of record-keeping — an inescapable problem whenever one works with the photographic medium, which has somewhat drifted to the margins of the field’s primary concerns (an awareness inherited from the previous generation of photographers such as Nakahira). By continually questioning how photography can possess resistance within a given era, he opens up the possibilities of photography as a means of confronting history and makes the condition of contemporary photography more acutely relevant”.

As mentioned earlier, in recent years Kitajima has also been highly active in the field of fashion photography. Through campaigns for Louis Vuitton and prolific fashion shoots for “AnOther Man” and “Vogue Japan”, he engages in a cross-disciplinary practice spanning fashion and art that is common among Western photographers but extremely rare in Japan.

“I was occasionally asked to do fashion photography for Comme des Garçons from a very young age, and then my requests for photography increased after I was asked to do it for Prada about 10 years ago.

I also started doing it through my relationship with Nick Haymes (a British fashion photographer based in Los Angeles. Kitajima has published a photobook with Little Big Man, the photography gallery Haymes runs, and Haymes also serves as photography director for “AnOther Man”). It’s interesting, but just because it’s fashion, I can’t say it isn’t my photography. At the same time, I can’t quite say it is my photography either. Maybe a time will come when I think that it is my photography. So, for now, it’s like a part-time job, I guess (laughs)”.

Calling it a “part-time job” sounds almost overly modest, given how outstanding the photographs of Rihanna for Louis Vuitton taken by Kitajima turned out to be.

“I was asked to do it by Nick’s wife, Lina Kutsovskaya (an art director), and it was tough. There were around 170 staff members at Warner studio in Hollywood. It was incredibly stressful. We had to wait five hours for Rihanna. I was thinking, what if I mess this up? But Rihanna was actually very easy-going, and we managed to shoot in a good atmosphere. And she was pregnant, wearing menswear (laughs)”.

While crossing from art to documentary and then to fashion, no matter what he photographs there is consistency that is unmistakably Keizo Kitajima-like.

“Basically, I’m just doing my work as an artist with Shinjuku Ni-chome as my base (laughs). Shinjuku Ni-chome is important. It’s better than Minato Ward, don’t you think? Being in a place like that makes it easier to go in all sorts of directions”.

Continuing gallery work and publishing independently, while also working with a giant major brand like Louis Vuitton...Kitajima’s activities convey the inherent dynamism of photography itself.

“I think that’s only natural. You know, I used to live in New York. Back then I went to the Mud Club on Canal Street, which wasn’t exactly safe, and major musicians would come there seriously looking for opening acts. That’s when I realised how closely connected the underground and the major scene really were.

If it’s only the major scene, there’s no energy, right? It’s more interesting to be on this side than on the major one. Photography isn’t fine art, and that’s a good thing, isn’t it? There’s fashion too...If it were only fine art, it would be completely boring”.

Kitajima once said that he “made photography boring in order to make it interesting”. For those who love photography, however, the very points he rendered “boring” are precisely what will feel deeply fascinating.

“Normally, what people call an interesting photograph becomes a matter of attributes, doesn’t it? A famous person being in the picture, or the value of fame itself. That’s different from the value of the photographic image. For the sake of the image’s value, those attributes have to be removed. That’s why my photographs are generally hard to accept. They’re difficult to understand. But that’s only natural”.

Kitajima deliberately strips away the attributes of photography in order to show the photograph itself.

“It may be impossible, but I want to show the image itself. To see whether it’s possible to reveal the very depths of the image”.